Great testing doesn't require programming skills. A great tester adapts and learns, regardless of their initial skillset.

Testing is...

... challenging. :-)

It's impossible to guarantee the discovery and resolution of all bugs, assess the significance of each issue, or ensure flawless functionality. The vast array of software and hardware combinations makes comprehensive testing unattainable. Failures can manifest in numerous ways, and even without apparent issues, an application may still fall short of expectations. Despite these difficulties, the aim is to guide the team towards the highest quality possible, considering the product and project context. This document serves as a concise introduction to the world of software testing, without any specific sequence. For additional resources, you can refer to the Wikipedia article on software testing or the ISTQB syllabus.

You can use the Wiki article for software testing or the ISTQB syllabus as a starting point.

Testing a feature

This is just a very rough approach for testing a certain feature. What you do in between is what actually counts for which the rest of this Handboook should provide plenty of inspiration.

- Examine all the specs and see if anything is missing

- Write test cases according to acceptance criteria

- Explore the feature freely

- Try the happy flows according to specs

- Try the unhappy flows and edge cases

- Check the design and interactions on several devices and/or browsers

- Do a smoke test of the rest of the app to quickly find out if anything else was broken

- Report any fresh issues

7 Basic Principles of the Context-Driven School

A balanced approach to software testing, taking into the consideration all aspects of a given project, will usually mean taking varied approaches depending on what the project calls for.

This means there is no silver bullet in software testing, but you can always take a hint from the context-driven school:

The value of any practice depends on its context.

There are good practices in context, but there are no best practices.

People, working together, are the most important part of any project’s context.

Projects unfold over time in ways that are often not predictable.

The product is a solution. If the problem isn’t solved, the product doesn’t work.

Good software testing is a challenging intellectual process.

Only through judgment and skill, exercised cooperatively throughout the entire project, are we able to do the right things at the right times to effectively test our products.

7 principles of software testing

Here's a more old-school list of software testing principles:

- Testing shows the presence of defects, not their absence

Testing can show that defects are present, but cannot prove that there are no defects. Testing reduces the probability of undiscovered defects remaining in the software but, even if no defects are found, testing is not a proof of correctness.

- Exhaustive testing is impossible

Testing everything (all combinations of inputs and preconditions) is not feasible except for trivial cases. Rather than attempting to test exhaustively, risk analysis, test techniques, and priorities should be used to focus test efforts.

- Early testing saves time and money

To find defects early, both static and dynamic test activities should be started as early as possible in the software development lifecycle. Early testing is sometimes referred to as shift left. Testing early in the software development lifecycle helps reduce or eliminate costly changes.

- Defects cluster together

A small number of modules usually contains most of the defects discovered during pre-release testing, or is responsible for most of the operational failures. Predicted defect clusters, and the actual observed defect clusters in test or operation, are an important input into a risk analysis used to focus the test effort.

- Beware of the pesticide paradox

Repeated tests become less effective at finding new defects, like pesticides losing their potency over time. To uncover new issues, modify existing tests and data, or create new ones. This paradox can have a beneficial outcome in cases like automated regression testing, resulting in fewer regression defects.

- Testing is context dependent

Testing is done differently in different contexts. For example, safety-critical industrial control software is tested differently from an e-commerce mobile app. As another example, testing in an Agile project is done differently than testing in a sequential lifecycle project.

- Absence-of-errors is a fallacy

Some organizations wrongly expect testers to run all tests and find all defects, which is impossible (principle 2). Simply fixing numerous defects doesn't guarantee system success; the system could still be user-unfriendly or inferior to competitors (principle 1).

Rapid Software Testing

Rapid Software Testing is a methodology and a class about it, authored by James Bach and Michael Bolton, focused on doing the fastest, least expensive testing that still completely fulfills the mission of testing.

Types of testing

Enumerating all possible software testing methods is challenging.

Defining a test can be nuanced. One perspective is that it's any interaction with software shedding light on its behavior under specific conditions. While this can spark endless debates, Michael Bolton's views on the topic are enlightening.

Have a look at Michael Bolton's opinion on the topic here.

For a pragmatic approach, let's consider categorizing the various types of tests available.

Note that this categorization may not encompass every conceivable test type.

According to approach:

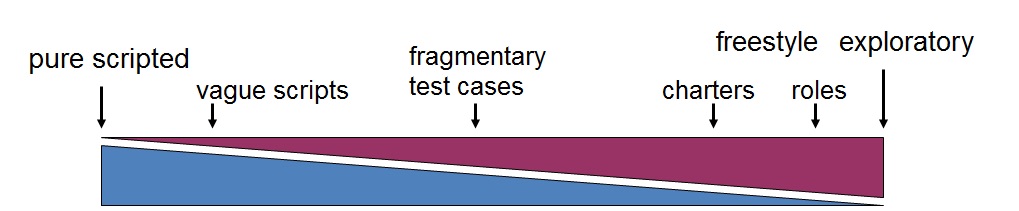

The way you test ranges from fully formal/algorithmic/scripted to fully random.

Script-based testing is slow and tedious, but good for confirming previously implemented functionalities are still working as expected.

Exploratory testing is faster at finding critical issues, usability problems, and unforeseen circumstances, but is usually incomplete and not fully reliable since it heavily depends on the tester's skill and experience.

According to focus:

Decide on your testing focus to maintain mental acuity, ideally honing in on one area. Broadly, this focus can be categorized into two groups: functional and non-functional testing.

Functional Testing: This aims to confirm that the application aligns with its intended behavior. When conducting functional testing, it's vital to adhere to task-specific requirements while also exploring potential shortcomings in these requirements.

Non-functional Testing: This type delves into aspects beyond the application's core functionality, which doesn't diminish its importance. This includes:

- UI testing

- Localization testing

- Usability testing

- Accessibility testing

- Performance/Load/Stress testing

- Security testing

- etc.

Bear in mind, these categories may not cover every aspect of testing but serve as a foundational guide.

According to scope:

Sometimes you don't want to test the entire app.

- Smoke/sanity/build verification testing

- Confirmation testing

- Regression testing

We use smoke testing to ensure the stability of a product build before proceeding with extensive testing. It serves to confirm that major, evident features are not severely malfunctioning.

Confirmation testing, on the other hand, validates whether a bugfix effectively resolves a known issue.

Regression testing is strategically applied at specific milestones in the app's lifecycle, such as before release, to detect overlooked edge cases that may not have been thoroughly tested during development.

What is exploratory testing?

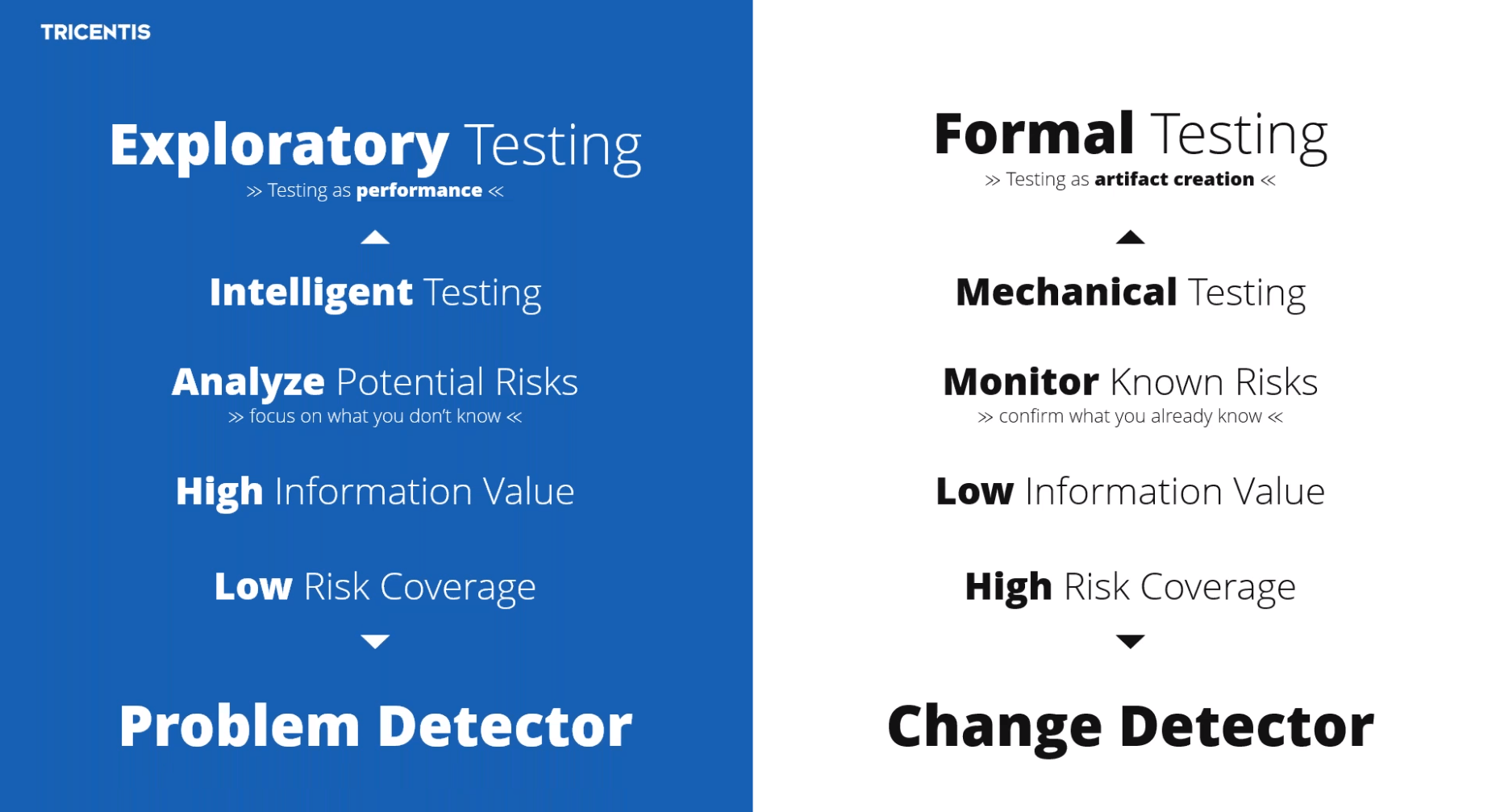

Exploratory testing is a swift and effective approach for uncovering software issues, but it isn't a free-for-all. It's akin to agile in contrast to the traditional waterfall method, as it drastically reduces preparation time by simultaneously designing and executing tests.

When engaging in exploratory testing, consider these steps:

- Allocate a specific time frame (e.g., 2 hours).

- Decide on the number of sessions and whether you'll test alone or with a partner.

- Define a clear testing goal.

- Choose an approach for testing.

- Keep a record of your questions, steps, and identified issues.

Sometimes, this planning is structured through an exploratory testing charter or visual aids like mind maps. The key is to investigate and freely explore your test objectives, adapting your planning method to suit your preferences.

Read more on exploratory testing from Cem Kaner or James Bach.

Types of testing - A fuller list

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it might just get you to dig deeper into certain areas that might help your software project.

How do other companies do testing?

See the howtheytest GitHub repo.