Story points in agile often feel like the extra pieces of an Ikea wardrobe that you are left with after you finished the assembly. The wardrobe is there, it stands straight, the drawers open smoothly, but you are left with a feeling of doubt. Should the pieces have been used somewhere? Somewhere important?

A useful metric in the agile toolbox

Similarly, your product is moving along according to plan, you are using scrum, all of the artifacts and ceremonies are there, but you are not using story points. Should you be The question sparks constant debate and there are as many opinions on the matter as there are JavaScript frameworks.

Story points are a useful metric for assessing the total effort required for bringing a product’s feature or functionality to life. They are part of the agile “dogma” and as such expected in most setups.

However, the lack of consensus on their value is due to a huge variety of use cases. Different agile teams and organizations may use them in completely different ways. This article tries to provide some insights into the matter and break down the benefits of using story points in project management.

Story points for estimates, hours for commitment

When a project is set in motion, the development team commits to a described block of work, also called a story. The team is then asked to give an estimate in hours or days to see if it fits the iteration they are working in.

By that point, the story should have already been refined to such an extent that all of the foreseen complexities and difficulties are – resolved, accepted, or eliminated (similar to ROAM). These complexities can include anything that might affect the outcome of the delivery, for example depending on a third-party software component, a complicated quality assurance procedure, lack of domain knowledge, vacation time, a missing flow, or just an especially large and complex chunk of work.

The success formula?

When taking on a story for development, the Dev Team is committing to deliver it in a fixed time frame – a sprint, release, or whatever other cycle they are working by. This is where one of the common misconceptions appears.

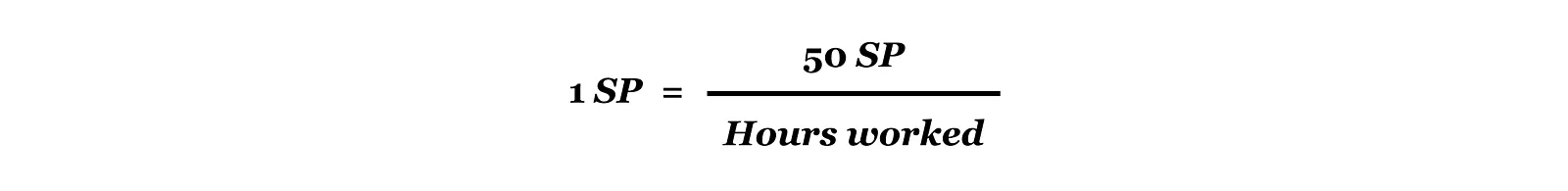

If a five-person team can deliver stories worth 50 story points in one sprint, does it mean that one story point can be calculated as 50 SP divided by the number of working hours?

No, it doesn’t and it shouldn’t. Yet we all know this happens often.

Story points are relative values

A story point can have different “weight” from person to person. However, in cross-functional teams, the number of story points committed to a cycle can vary greatly depending on the type of work and team composition. This does not mean that story points are useless from the perspective of a development team.

Hour estimates deal with the uncertainties and complexities of a task in a way that they increase the total amount of time needed for implementation.

The problem with that approach is that not all complexities can be handled with time. We add buffers and give out ranged estimates, but after a certain point the message should simply be “we are not sure”.

When stakeholders see a large number next to a work item, first they assume it’s hours or something that can be translated into hours. They recognize it as complex, requiring a lot of effort, but they also see a commitment to deliver within a limited timeframe.

Ideally, story points should bridge the gap in the Dev Team – Scrum master – Product Owner – Stakeholders communication chain. They provide a new criterion for describing a set of tasks, and focus not only on the estimated time needed to complete it, but on how demanding it is.

Moving away from hours to story points should make the difference between commitment and complexity clearer and more understandable.

The numbers dilemma

Let’s illustrate why numbers are a problem with an extremely simplified example. Most people in software development have probably been in this kind of situation at some point.

The development team delivered a total of 34 story points in the last sprint and they closed off 34 work items. Planning the next sprint with the stakeholders/product owner, you come upon a work item in the backlog that was estimated at 34SP at some point. It organically comes to mind that this could fit perfectly into the next sprint, right? Wrong. It might, but it might not.

Unless your environment is a high-functioning, development-oriented, agile organisation, using numbers for story points might become troublesome. You can Fibonacci all day but explaining that it’s about proportions, not the value itself, and that 5 SP is not really five of anything, will not intuitively make sense to most people.

It may be helpful to use T-shirt sizes (S, M, L, XL, XXL), although some pitfalls apply here as well. Still, it seems to cause less confusion than SP numbers.

Using story points for the development team can be an effective way of communicating to the product owners and stakeholders which stories need to be worked on and refined.

If your use of story points in the form of numbers gives the misleading impression of certainty and commitment, then change them to whatever gets the message of complexity across, even if it’s simply an all-caps statement saying: THIS HERE IS COMPLICATED!

You can also create your own framework, for example range the complexity levels as foes from Lord of the Rings and their difficulty to defeat:

- Orc – simple and straightforward

- Uruk Hai – overall simple and straightforward, numbers could be a problem

- Troll – challenging but manageable, needs some planning

- The Witch King – problematic, definitely needs a plan, victory depends on very vague documents and prophecies, would not take on lightly

- Balrog – if a problem requires a solution in the form of one of the mightiest wizards in Middle Earth, we probably need to discuss it in a lot more detail

- Sauron – key elements missing – ring, volcano, team, giant eagles…

The way to work with this is to break down any Sauron-level stories to Trolls or simpler if possible.

What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow?

Scrum Masters need story points to create velocity charts. Besides using them to indicate team performance and productivity, Scrum Masters limit the work committed in a cycle based on the velocity from previous cycles. They calculate velocity because they are often asked when and how much the development team can deliver.

For this to have any practical value, a number of factors need to remain constant, like team size, team composition, domain knowledge, etc. (Cross-platform teams and an agency setup can make this consistency hard to achieve, but that’s a different topic.) Without consistency, velocity charts are just a divination tool, sort of like an astrological chart for development team deliveries.

The people asking “when and how much” are the Product Owner and the Stakeholders. Now there is an entangled web of managing expectations, adding business value, keeping the product maintainable and scalable while having a clear and visible plan for implementation. It’s a continuous loop where visibility and transparency are the key to a successful relationship and finally, successful product development.

When story points are used effectively, it should also result in a well-defined backlog of stories.

These can be easily picked up for implementation in the next development cycle. Further, we give the stakeholders a clear overview of what can be immediately prioritized for development and what needs to be ironed out.

Effective, when used wisely

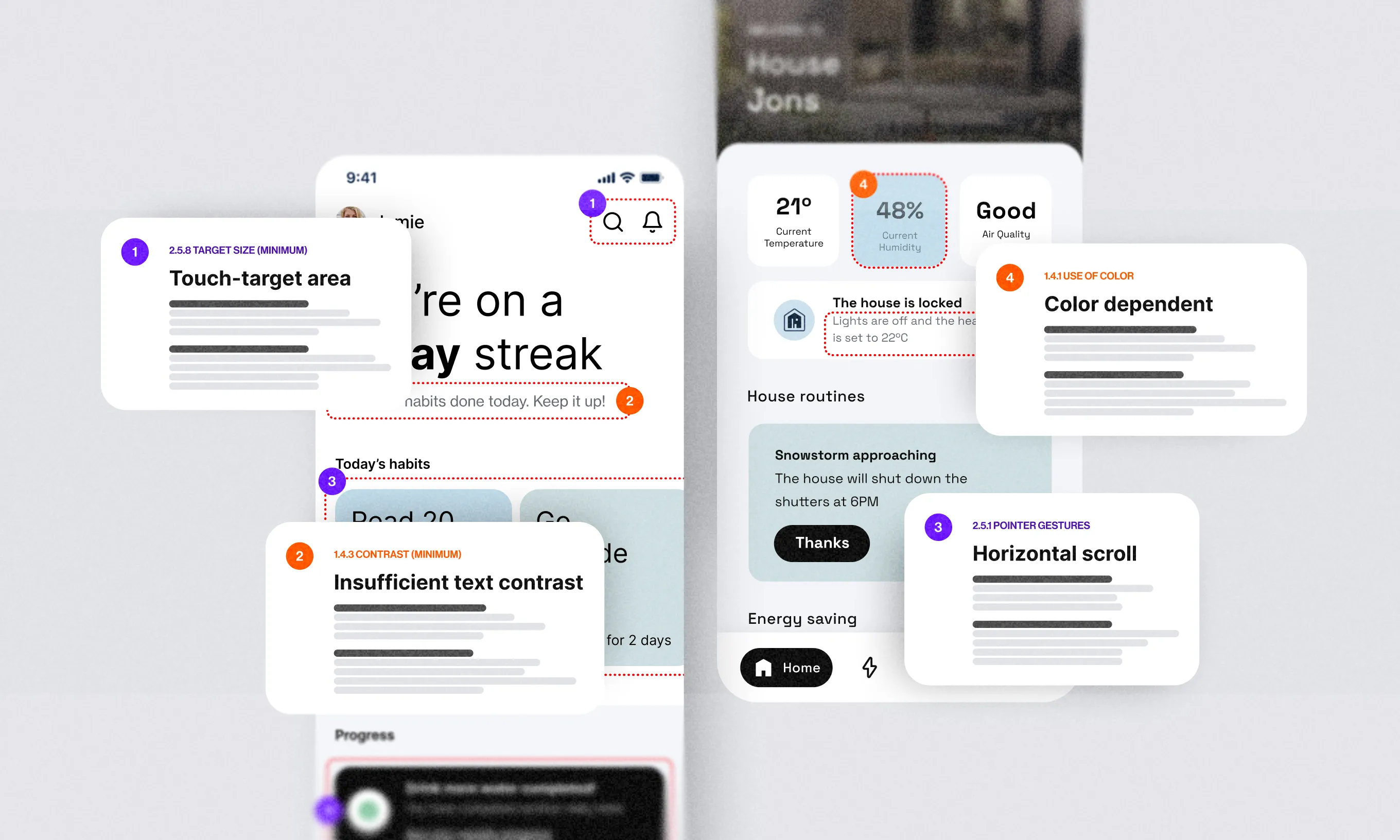

Story points are a tool that should reduce miscommunication and misunderstandings. They should also help draw attention to those stories that need more work before you can consider development. That is the key to the effective use of story points – they shift the focus from what can be delivered and when, to why the complexity is so high and how PO’s can help reduce it.

Hopefully, this clarifies some of the aspects of using story points in the agile framework. How these relate to the actual effort put in for each step is a whole different story to tell.