AI is changing how software gets built: faster timelines, leaner teams, fewer blockers. But does all that speed come at a cost? We put AI to the test in a real-world security experiment, and what we learned should matter to anyone leading modern product, platform, or tech teams.

According to Collins Dictionary, vibe coding is officially the word of the year – and if you’ve spent literally any time around engineering teams lately, that probably doesn’t surprise you.

Obviously, it’s catching on fast.

Microsoft recently shared that around 30% of the code in some of its repositories is now AI-generated.

At Infinum, we see this trend up close, both in internal experimentation and in conversations with clients who are increasingly curious about AI-assisted development.

The appeal is clear: development is faster, prototypes turn into products at record speed, and teams feel confident shipping.

But is that confidence earned? We decided to find out.

Security doesn’t work on vibes

A growing belief is quietly taking hold in many teams:

“If I tell the AI to make it secure, it probably will.”

That assumption is understandable because AI is very good at reproducing patterns that look correct. When prompted, it can generate code that resembles common security practices and includes familiar terminology, giving the impression that risk has been addressed. But is it, really?

Instead of debating, our cybersecurity engineer designed a simple, hands-on experiment.

He asked AI to build apps with varying levels of security guidance, from none to OWASP-level detail, and then he tried to break them.

We didn’t want to test whether AI could write code. We know it can.

Likewise, the goal wasn’t to assess if AI builds insecure apps by default. We wanted to test whether adding “make it secure” to your prompt is enough to stop vulnerabilities – and how that changes as you get more specific.

Let’s see the results.

The apps we built (and broke)

We asked AI to build three medium-complexity web applications, realistic enough to offer an attack surface, but not so complex that AI failed to build them. One app was generated with no security input at all, one with light guidance, and one with detailed, best-practice-driven instructions.

| App | Security guidance | Security quality | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Project Tracker – task and project manager for small teams | None | Poor | Multiple critical issues in input validation, design, and session handling, easily leading to worst-case exploitation scenarios. Users could make themselves admins. |

| Project Resource Hub – internal portal for sharing documents and guides | Light | Mixed | Critical issues reduced, but several vulnerabilities remain that could still expose sensitive information, such as SSRF and malicious file uploads. |

| Niche Vault – hobbyist catalog site for personal collections | Detailed & OWASP-based | Better, but insufficient | Significantly fewer vulnerabilities; none severe, but still issues that could pose risks over time. Missed CSV injection, rate-limiting, and open redirects. |

Turns out, not even specific prompts are enough to build applications that can survive real-world attacks.

What actually went wrong

Even with better prompts, the same kinds of security gaps kept popping up.

AI didn’t forget libraries or miss syntax. It just couldn’t reason about how things might go wrong, and that’s where real-life threats were.

AI didn’t forget libraries or miss syntax. It just couldn’t reason about how things might go wrong, and that’s where real-life threats were.

While we are aware that this is an experiment of a limited scope, it is still important to note recurring issues we recognized:

Trust in user input

AI simply trusted what users said about themselves. In multiple apps, user roles (such as admin) were accepted directly from client input, with no validation or enforcement. If someone claimed to be an admin, the system said: “Sure, sounds legit.” Just like that, admin access was self-serve.

Broken or missing access control

Even when roles were assigned correctly, features didn’t enforce them properly. There were no ownership checks, no context validation, no guardrails. Anyone logged in could view, modify, or delete other users’ data.

Feature-level defenses, system-level blind spots

AI knew to sanitize an input field, but it didn’t think about how that input might travel through the system. Security was applied in pieces, not as a pattern, which means defenses weren’t absent; they were just easy to step around.

Reactive security instead of proactive thinking

The apps didn’t lack rate limiting, but rate limiting was only added to endpoints the prompt specifically called “sensitive.” In other words, if you want a feature to be secure, you have to explicitly tell the AI – every time.

No imagination for abuse cases

And this might be the most important insight of all: the AI assumed good-faith users. It never asked the question that is the foundation of real-world security: What if someone does the wrong thing on purpose?

In conclusion, the issues discovered weren’t bugs in the traditional sense. They were assumptions – that roles are respected, that the app can trust user input, that attackers won’t be creative.

Most of the problems were not broken locks, but doors that simply weren’t locked because AI assumed nobody would try them.

HRVOJE FILAKOVIĆ,

CYBERSECURITY ENGINEER

But attackers are creative, and they have all the time in the world to look for what you missed.

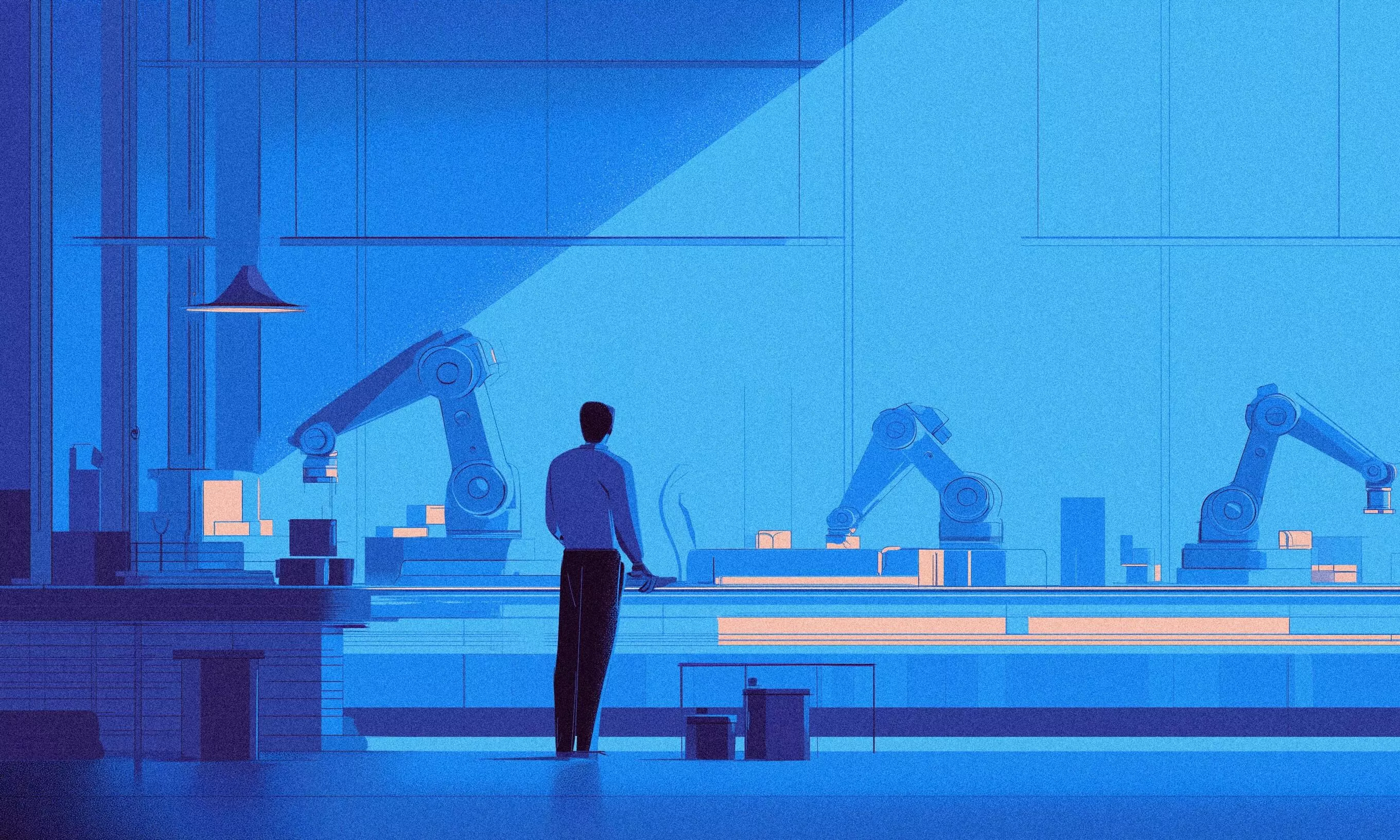

Why this matters beyond the code

Security is not just a dev problem. It’s a systems-thinking problem, and it affects every role involved in shipping software.

For CTOs & Heads of Engineering

AI speeds things up, no question, but it can’t replace architectural thinking.

The biggest failures in these apps weren’t in the code; they were bad assumptions about how trust, roles, and permissions work. Even when AI adds security controls, it struggles to secure the system as a whole.

We’ve all recently witnessed this: in our deep dive into OpenClaw (ex Moltbot), we explored what happens when AI sidekicks are given broad access with no guardrails. The takeaway? When AI has too much control, your data is very likely at risk.

Again, that’s an architectural one. And it’s still up to humans to get it right.

For Founders & Execs

All three apps worked. Some even looked secure. But they could still be exploited in serious ways, often through features that seemed harmless.

Remember this: AI gives a false sense of security. Without hands-on testing, issues like these show up only after damage is done.

For Security Leaders

The vulnerabilities we found didn’t have CVE numbers. They weren’t from outdated libraries or missing headers. They were logic and abuse-case failures – the exact kind of problems automated scanners don’t catch.

Manual penetration testing still matters because it mirrors how attackers behave, not just what vulnerabilities exist – and AI-assisted code makes this more important, not less.

For Developers

AI can implement what you tell it, but it’s not a security expert. It won’t catch logic flaws, system-wide assumptions, or the creative misuse attackers are known for.

Writing secure apps still requires developer intuition, threat awareness, and curiosity about how features might be abused.

The key takeaway: “Please make it secure” is not a security strategy. AI can help you build faster only if you know exactly what to ask for, and even then, it often misses the bigger picture.

So, yes. AI-generated code can be secure, but it takes judgement, experience, and most importantly, testing.

What should you do now

Use AI. Embrace the speed. Build more, experiment faster, prototype wildly.

But don’t confuse working code with secure code.

- Bring in experienced engineers. Secure software doesn’t just happen, it’s built intentionally. SSDLC practices are more essential than ever when code is being generated at speed.

- Test like an attacker. Manual penetration testing reveals what AI misses: the logic flaws, the edge cases, all the blind spots that open into serious vulnerabilities.

Why automated scanners won’t help

Automated tools catch known and “low-hanging fruit” types of vulnerabilities. But issues discovered in this experiment weren’t in any vulnerability database, because they weren’t traditional bugs – they were incorrect assumptions about how systems would be used.

The AI knew the best practices, it just couldn’t connect the dots to anticipate misuse. That’s what manual testing is for – to expose unknown risks.

Automation wouldn’t have caught that, but manual testing told us whether the system could survive a curious attacker.

The real takeaway

The apps worked and security looked reasonable.

But AI inherently doesn’t understand security, which is especially obvious once software interacts with real users, real data, and real incentives to misuse it. Security failures rarely come from missing syntax or forgotten libraries; they emerge from incorrect assumptions about behavior, trust, and intent.

- AI builds what you ask for.

- It protects what you explicitly mention.

- It doesn’t secure the system as a whole.

- It doesn’t imagine creative misuse.

Attackers do nothing but imagine misuse.

This is exactly why manual penetration testing exists: not to check a box, but to ask the one question that AI won’t:

“What happens if someone does the wrong thing on purpose?”

Security still requires human intent and adversarial thinking. No matter how well you prompt it, AI can’t protect against what it doesn’t anticipate.

If your app was built with AI assistance, this isn’t a theoretical risk. It’s a structural one.

If you want real, certified humans to have a go at your app – partner with Infinum’s security team to test your app the way real attackers would. We’ll help you find the blind spots, close the gaps, and build safer systems, so you can move fast without leaving yourself exposed. If we find zero issues, the beer is on us.