When defining software architecture, we always want to achieve certain characteristics. For our team, the focus is on flexibility, reusability, and testability. We are guided by these characteristics but are not restricted to them. The main purpose of project architecture is consistency among projects, which makes sharing knowledge and the transition of people among projects easier. We also prefer architecture that helps with standard framework issues or makes them easier to solve. In fact, this was a huge motivation to ditch the old MVP and switch to a new MVVM project architecture. Although this chapter covers the MVVM architecture specifically, all of the concepts and good practices mentioned in the general Mobile app architecture chapter apply here as well.

What is MVVM?

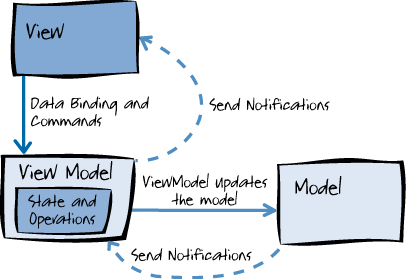

Today, MVVM is a well-known architecture that was developed by Microsoft and publicly introduced in 2005 (source: Introduction to Model/View/ViewModel pattern for building WPF apps). It consists of three components: Model, View, and ViewModel. Let's take a more detailed look at the components:

- The Model in MVVM has the same role as in the MVP architecture. It is responsible for managing the data received from a specific data source (Database, Network) and completely UI independent.

- The View in M*V*VM also has a similar role as in MVP—presenting data to the user. In Android, the View is usually represented as an Activity, Fragment, or an Android view. The key difference between the View in MVP and in MVVM is that the MVVM View has more knowledge about the underlying Model and ViewModel in the sense that it knows about the events and states that have to be observed.

- The ViewModel in MV*VM* is also known as the "Model of a View" and can be considered a View's abstraction that creates a link between the Model and the View. The difference between the Presenter from MVP and the ViewModel is that the Presenter has a reference to a View, whereas the ViewModel directly binds to properties on the View Model to send and receive updates.

Architecture components

Android architecture components are a collection of libraries that help you design robust, testable, and maintainable apps. They serve as the main guideline in building the backbone of our project architecture. By using Android architecture components we don't have to worry much about managing the app's lifecycle or loading data into our UI. This helps us focus on important and cool stuff in the project.

ViewModel

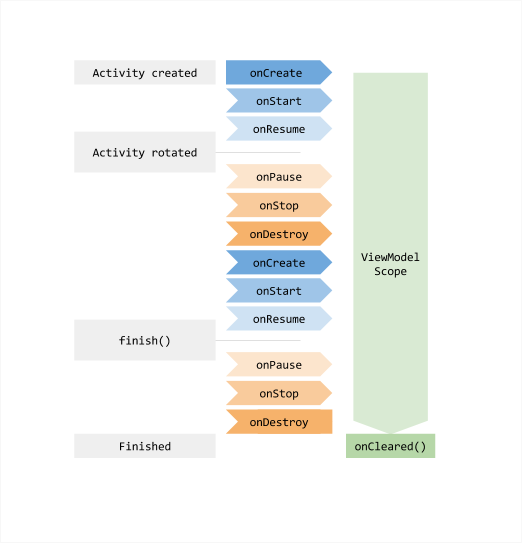

ViewModel is an important part of the architecture, and it represents the pillar of our business logic. ViewModel's main purpose is to store and manage data for UI. It is designed to survive the activity configuration changes, screen orientation being the most common and troublesome one. The below image displays the scope of the ViewModel and its lifetime in memory, with the lifecycle states of an activity as it undergoes rotation and then is finished.

The ViewModel might sound powerful, but this is just a simple abstract class in the architecture components library. The magic stuff resides in the ViewModelProvider. ViewModelProvider is responsible for the creation and retention of the ViewModel. To create a ViewModelProvider for a specific Activity/Fragment, you should use the ViewModelProviders util class.

LiveData

LiveData is a lifecycle-aware observable class that is used as a medium for data transfer from the ViewModel to the View. Because of its connection to the activity lifecycle, the number of memory leaks, crashes, and lifecycle synchronization events between architecture layers has been reduced. LiveData will take care of notifying the View about the latest data when the time is right. We only take care of preparing the correct data.

LiveEvent

As LiveData is not best suited to handle the problem of resubscriptions in some use cases (Snackbar, Navigation, and other one-shot events), Google added a custom implementation of LiveData called SingleLiveEvent in the Android Architecture Blueprints. It is a lifecycle-aware observable that sends only new updates after subscription, used for events such as navigation and Snackbar messages. For more information regarding this topic, please read this article. However, the SingleLiveEvent implementation from Google has one major setback—it works only with one observer at a time. This issue is addressed and explained in detail in this article. The author of the article proposes an improved implementation, called LiveEvent, which covers the case of multiple observers. The source for implementation: LiveEvent.

Flows

Flows are conceptually a stream of data which flows in a pipe and can be computed asynchronously. On both ends of that pipe, there is a producer and a consumer running on coroutines (flows are built on top of coroutines). Suspend functions return only a single value and flows come in handy when we need to emit multiple values sequentially.

StateFlow and SharedFlow

StateFlow and SharedFlow are Flow APIs which we use to enable flows to optimally emit state updates and emit values to multiple consumers.

By definition,

StateFlow is a state-holder observable flow that emits current and new state updates to its collectors.

Essentially, StateFlow is very convenient for keeping our view states. It is a great fit for maintaining observable mutable states and handling live state updates.

On the other hand, SharedFLow is a highly-configurable generalization of StateFlow.

All methods of SharedFlow are thread-safe and can be safely invoked from concurrent coroutines without external synchronization.

SharedFlow is the perfect choice when dealing with events. With SharedFlow, we avoid the trouble of handling resubscriptions (the cases when we want to do a certain action only once, such as showing toasts, Snackbar, navigating between fragments, etc.). SharedFlow behaves as a hot flow and it emits values to all consumers that collect from it.

LiveData vs Flow vs StateFlow vs SharedFlow

Since Kotlin Coroutines introduced StateFlow and SharedFLow, these types have opened the opportunity for substituting LiveData and they are becoming the go-to types for handling states and events. Additionally, they also solve the problems which appear when using pure Flows for this purpose (pure Flows are stateless and declarative (cold), therefore, they are not very suitable for working with states and events).

Coroutines have dominantly taken over Rx and the major drawback of LiveData is that it is not built on top of coroutines, unlike the StateFLow and SharedFlow. LiveData is closely bound to the UI and the Android platform, it is lacking control over the execution context and there is no natural way to offload some work from the worker threads. Everything that you can do with LiveData can be done in a much more elegant and improved manner by using the hot streams, StateFlow and SharedFlow. A major difference from LiveData is that they are not lifecycle aware, however, this can be easily solved by using repeatOnLifecycle APIs. In the end, we can see that StateFlow and SharedFlow cover all the disadvantages and limitations that come with LiveData implementation. However, this doesn't mean that LiveData should be entirely excluded from projects or that it will become deprecated soon.

Now that we understand how superior StateFlow and SharedFlow can be, let's see their difference. By default, SharedFlow takes no value and emits nothing, whereas, StateFlow takes a default value through the constructor and emits it as soon as someone starts collecting it. StateFlow is a subtype of SharedFlow, therefore, it has more restrictive configuration options. StateFlow follows the concept of single current value. It must have an initial value because, otherwise, it would break the principle of always having a current value. Moreover, for the value to be single, it means that the replay always has to be 1 and it is not possible to create a buffer aside from the one current value.

A general guideline would be to use StateFlow for working with states and SharedFlow for working with events.

What is also worth mentioning is the Channel. SharedFlow will emit data even if no one is listening, whereas, Channel will hold the data until it is consumed. In a situation where a SharedFlow emits an event and the view is not ready to receive that event, the event is lost. Thus, channels could be an even better solution for sending one-time events.

For a more detailed comparison, check out this article.

What is solved with MVVM?

- Canceling network calls

Since we have LiveData to take care of lifecycle state changes, we don't have to worry that much about the async work that loads our data. We can set the data to LiveData at any time without fear that it's going to crash our app because the View is not ready. This means that there is no need to cancel a network call when activity is moved to the background. So, no unnecessary data traffic, repeated calls, checks if we already have the data, or in-memory cache in the activity scope.

- Recreating an activity and state preservation

The ViewModel together with all the data will survive the activity configuration change. LiveData will again handle the lifecycle state. The View will be up to date. The API will not be bothered with any of this. The developers will be happy for the rest of its life. OK, let's not go that far; we still need to use fragments. :)

- Flow control

Most applications contain some screens that can be grouped into a flow. Inside this flow, you will often have to share some data. Information from the previous screen might be needed or might influence some of the future screens. The ViewModel and LiveData can be the perfect solution for such situations. If you organize a specific flow inside one activity and all other screens as a fragment, it is easy to share a ViewModel among all fragments and the controlling activity. This makes it easy to share, store, combine, and manage all the data in the flow.

Coroutines vs RxJava

Asynchronous code has always been one of the most challenging topics when developing Android apps. For a very long time, RxJava, with its most important building blocks - Observables and Subscribers, helped us achieve everything we had to in order to have asynchronous and event-based programs. RxJava, as its name suggests, is meant for any Java compatible language. Kotlin does fall into the category of Java compatible languages, however, since it has become very popular in the Android development community, eventually, the need for some Kotlin specific way of handling asynchronous work arose. This is how Kotlin Coroutines were born.

A coroutine is a concurrency design pattern that you can use on Android to simplify code that executes asynchronously. Coroutines help to manage long-running tasks that might otherwise block the main thread and cause your app to become unresponsive.

Nowadays, coroutines are significantly dominating over other solutions (such as RxJava) for asynchronous programming in Android. Coroutines are extremely lightweight (due to their support for suspension - ability to run many coroutines on a single thread) and they have built-in cancellation support. On top of that, coroutines lead to fewer memory leaks (by using structured concurrency) and they provide a nice Jetpack integration.

Using coroutines and Kotlin for Android development goes hand in hand. If you are using RxJava our suggestion would be to migrate to coroutines. To help you with migration you can covert RxJava code to coroutines using libraries like kotlinx-coroutines-rx3

Implementation

This section will go through some main guidelines on how to implement MVVM in your Android project. We will cover the implementation of MVVM using the architectural components from Android we described in an earlier section.

The user interface in an Android app is made from a collection of View and ViewGroup objects that are located inside of an Activity or a Fragment container. Those two containers represent the View component in the MVVM architecture. You may wonder why an ordinary Android View could not be the View in MVVM? This is a totally valid question, and it can be implemented in many ways, but we will focus on Activities and Fragments because they both implement the LifecycleOwner interface, which gives us an opportunity to use LiveData and ViewModel. Using LiveData and ViewModel gives us a great head start in developing our MVVM architecture.

Let's take a look at the ViewModel first. It is probably a good idea to have a base implementation of the ViewModel that will handle some shared logic and reduce the boilerplate in our codebase. It will look something like this:

open class BaseViewModel: ViewModel()

Now we need a means of communication between the ViewModel and the View. But before we write about that, let's see what kind of information our View expects in the communication. In other words, what should we expose to the View from the ViewModel?

In most cases, the View wants to know about the state of the screen so that it can render the changes accordingly. The state of the screen is an object that represents stateful data that the user can see on the screen. To better understand what is part of the screen state, you can look at it in the following way. A part of the state can be any data representation of a UI component that we want the View to render after it is recreated. The end goal is to have the same screen like the one before the View got recreated.

Unlike states, there are things that we do not want to render after a View recreation. For example, displaying self-dismissible messages (Toast, Snackbar, etc.) or some kind of navigation triggers. For this, we need to expose another piece of information to the View, and we call them events. An event is a one-shot trigger that is emitted from the ViewModel and consumed by the View only once.

Considering the concepts of the State and Event, we would adjust our BaseViewModel implementation to be aware of them. The end result would look like this:

open class BaseViewModel<State : Any, Event : Any> : ViewModel()

We now have the state and events for a specific View, but we are still missing a way to expose these objects to the View. This is where LiveData and LiveEvent implementations come into play. Inside the ViewModel, we need the LiveData objects of state and events that the View can observe. LiveData objects would look something like this:

open class BaseViewModel<State : Any, Event : Any> : ViewModel() {

private val stateLiveData: MutableLiveData<State> = MutableLiveData()

private val eventLiveData: LiveEvent<Event> = LiveEvent()

fun viewStateData(): LiveData<State> = stateLiveData

fun viewEventData(): LiveData<Event> = eventLiveData

}

As you can see in the code above, we expose our private stateLiveData and eventLiveData through functions that return immutable LiveData. This way, we make sure that we do not allow changes to be made to our LiveData objects directly, but, at the same time, we allow observing changes made on our LiveData objects.

To make it easier to use LiveData objects, we can create a convenient backing field and function that will help us manipulate LiveData objects in our specific ViewModel implementation.

open class BaseViewModel<State : Any, Event : Any> : ViewModel() {

//...

protected var viewState: State? = null

get() = stateLiveData.value ?: field

set(value) {

val viewState = stateLiveData.value

stateLiveData.value = value

}

protected fun emitEvent(event: Event) {

eventLiveData.value = event

}

}

When we have a BaseViewModel implementation, for example LoginViewModel, we have to provide it to the View. This can be achieved using a utility method from the ViewModelProviders class:

ViewModelProviders.of(this).get(LoginViewModel::class.java)

In the above code, this represents the LifecycleOwner. In our case, as mentioned earlier, this is either an Activity or a Fragment. The above code returns a ViewModel instance which we use to observe LiveData objects.

loginViewModel.viewStateData().observe(this) { state ->

// Update the UI state

}

loginViewModel.viewEventData().observe(this) { event ->

// Handle event

}

This is now enough to establish a connection between the View and ViewModel.

So far, we've only concentrated on the View and ViewModel, but what about the Model in MVVM? The Model is responsible for managing the data received from a specific data source (Database, Network, etc.), completely UI independent. This means that the Model should expose its data only to the ViewModel. The ViewModel can also request some data from the Model, so it is a two-way communication.

Implementation using StateFlow and SharedFlow

If we want to use StateFlow and SharedFlow as a substitution to the LiveData objects mentioned above, our BaseViewModel will look something like this:

abstract class BaseViewModel<State : Any, Event : Any>(private val initialState: State) : ViewModel() {

val state: StateFlow<State> get() = stateFlow

val commonState: StateFlow<CommonState> get() = commonStateFlow

val event: SharedFlow<Event> get() = eventFlow

private val stateFlow: MutableStateFlow<State> by lazy { MutableStateFlow(initialState) }

private val commonStateFlow = MutableStateFlow(CommonState())

private val eventFlow: MutableSharedFlow<Event> = MutableSharedFlow()

}

The private properties stateFlow, commonStateFLow, eventFlow are mutable only within the BaseViewModel and we expose them through the properties state, commonState, event which are immutable.

A backing field and function would be really helpful for using these objects inside our ViewModels which inherit from the BaseViewModel, therefore, in our BaseViewModel we will add the following code:

abstract class BaseViewModel<State : Any, Event : Any>(private val initialState: State) : ViewModel() {

//...

var viewState: State

get() = state.value

set(state) {

stateFlow.value = state

}

protected suspend fun emitEvent(event: Event) {

eventFlow.emit(event)

}

}

In the Activity or Fragment, we will handle the states and events and adjust the UI accordingly.

At this point, the concept of MVVM and how to implement it should be much clearer and easier to understand. Take into account that the code you saw was very simplified, just to show the conceptual idea of MVVM in Android. This is only one way to implement it, there are many more different kinds of implementation that may include DataBinding or are very Rx heavy.