When our apps work well, our users are happy. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. Instead of striving for a perfect world of no crashes and no errors, our goal should be to make the best effort in effectively diagnosing and quickly fixing issues.

At Infinum, we’ve worked on hundreds of mobile apps. Fixing crashes is our day-to-day activity. In this guide, we will cover our learnings and best practices of good crash reporting and error handling.

Application errors

“Errors are a fact of life in software”

Swift has a powerful error-handling mechanism, which can in a great deal help us write robust and resilient apps. But, as with all language features, we need to use it right.

From the application perspective, there are two types of errors it can encounter:

1. Expected

2. Unexpected

Expected errors

Expected errors are usually handled as part of regular application flow.

Example 1

The user uploads a document to the backend but the backend needs some time to process it.

In this case, the application might implement API polling. API can return a 404 error to indicate that the resource is not yet available. The application can retry an API call until it gets a 200 response code.

Example 2

Under bad network conditions, the user attempts to download a file.

In this case, the application might implement an automatic retry mechanism to make it more resilient to failures.

Typed errors

“Errors are generally propagated and rendered, but rarely handled exhaustively, and are prone to changing over time in a way that types are not.”

Whether your APIs are using Combine, Result type, or recently accepted typed throws, you might be inclined to define something like:

enum MyAppError {

case network

case invalidInput

// ...

}

And expose explicit error types in your APIs. This is generally not advisable as it will limit your ability to compose. You might as well find yourself in a situation where you are constantly adding error cases to MyAppError enumeration.

However, when used wisely, in some cases, we can end up with elegant APIs. For example:

enum ResourceError: Error {

case notAvailable

case error(Error)

}

func checkIfResourceAvailable() -> AnyPublisher<Void, ResourceError> {

fatalError()

}

func waitUntilAvailable() -> some Publisher<Void, Error> {

checkIfResourceAvailable()

.tryCatch { error in

switch error {

case .notAvailable: waitUntilAvailable()

case .error(let error): throw error

}

}

.eraseToAnyPublisher()

}

It is important that these are very localized use cases that don’t propagate typed error information upstream. Upstream code is usually interested in generically handling errors.

Unexpected errors

“An error has occurred.”

Unexpected errors are the ones that applications cannot handle in a meaningful way. Usually, the application has no better way to handle these errors than by displaying them to the user.

Make illegal states unrepresentable

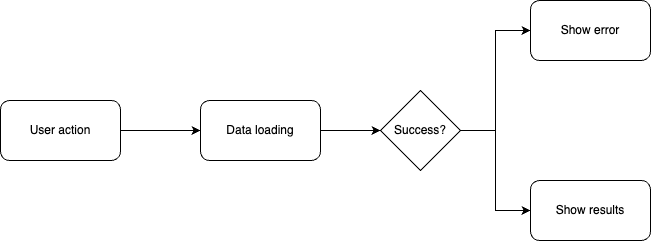

Errors usually occur in response to some user action. More generally, this interaction can be visualized in the following diagram:

In this diagram, we have 3 mutually exclusive states of our program:

Data loading is in progress

Data is successfully obtained

There was an error during the data loading

To provide a consistent experience, it is useful to represent this idea in code explicitly. In SwiftUI, we can define something like:

enum Loadable<Value> {

case loading

case failure(error: Error)

case success(Value)

}

struct LoadableView<T, U: View>: View {

let element: Loadable<T>

@ViewBuilder let onSuccess: (T) -> U

let onRetry: (() -> Void)?

var body: some View {

switch element {

case .loading: LoadingView()

case .failure(let error): ErrorView(error: error, onRetry: onRetry)

case .success(let value): onSuccess(value)

}

}

}

This allows us to handle loading, error, and success states generically and consistently throughout the app.

ErrorView can look something like this:

struct ErrorView: View {

let error: Error

let onRetry: (() -> Void)

var body: some View {

VStack {

Image(.error)

Text("An error has occured")

Text(error.localizedDescription)

Button("Retry") { onRetry() }

}

}

}

This way, users will always see localized descriptions of the error, and they will be able to retry the operation.

This pattern can either be applied to the whole screen or partially, to some of its elements.

Error mappings

To ensure this pattern works well, all your errors should conform to LocalizedError and provide a meaningful message to the user.

Unfortunately, in many cases, we will get an error from some API in either 3rd party SDK, or iOS SDK. If it is important to provide a human-readable message in those cases, you will need to handle those errors explicitly and provide your error message.

One such special case can be no internet connection state. The code that handles it might look like this:

struct NoInternetError: Error, LocalizedError {

var errorDescription: String? { "Please check your internet connection" }

}

extension Error {

var asNoInternet: NoInternetError? {

switch (self as NSError).code {

case NSURLErrorNotConnectedToInternet, NSURLErrorDataNotAllowed:

NoInternetError()

default:

nil

}

}

}

API errors

If your app is using backend APIs, most likely, this will be the main source of errors. Try to define an error body contract with the backend team. This will transfer the ownership of error messages to the originator. The backend has more context required to return a good error message to the user.

struct ErrorResponse: Decodable, Equatable, Sendable {

let code: String

let title: String

let detail: String

}

struct APIError: LocalizedError {

let code: Int

let response: ErrorResponse?

var errorDescription: String? { response?.title }

}

This can be optionally parsed from the response of URLSession and thrown as a more detailed error:

func fetch(request: URLRequest) async throws {

// ...

guard response.statusCode >= 200 && response.statusCode < 300 else {

let response = try? JSONDecoder().decode(ErrorResponse.self, from: data)

throw APIError(code: response.statusCode, response: response)

}

Be careful in API design

“We still focus so much on our experience of the use of the construct”

We all prefer convenient and easy-to-use APIs. But we need to be aware of what is hidden behind.

For example, it might be tempting to expose Keychain API as a property wrapper. That would allow us to do something like this:

class User {

@KeychainValue("token") private var token: String?

}

This is very expressive code, where, in one line of code, it is clear that we are dealing with a keychain item that automatically gets serialized and deserialized to the keychain.

Unfortunately, with such an API design, we fundamentally limit our program to handle keychain errors.

The reason for this is that the underlying keychain API returns the status of the operation being performed. And by exposing such an API as String? we effectively map all errors to optional values.

The same advice follows for choosing libraries. Understand what you get by integrating a library.

Debugging errors in production

We can summarize this in few simple rules:

Always preserve the original error. If you need to transform it, wrap it inside of your custom error

Avoid using

try?unless the operation is truly optional. This is rarely the caseAvoid returning optional when an error should be thrown

Conform your errors to

LocalizedError

If we follow these rules, we get some nice side effects:

Users will always see localized descriptions

We will preserve the original errors with all the details (such as HTTP status code or framework error)

Error details

Users are generally interested in human readable descriptions of the error. But for programmers, it is critical to have as much details as possible about the error.

We can expose these details in our ErrorView by providing an additional Details button. If you can’t do that in production, it might be a good idea to enable detailed error handling at least in staging builds.

This can simplify finding issues and shorten the feedback loop between the person reproducing the error and you.

Non-fatals

Firebase non fatals are a great way to get more detailed information about errors that occur in production. This can usually provide critical information for debugging user-reported issues. To utilize and analyze them effectively, we need to have fine fine-grained grouping of errors.

As mentioned in the Crashlytics guide:

“Unlike fatal crashes, which are grouped via stack trace analysis, logged errors are

grouped by domain and code.”

This means that, to group Swift errors properly, we need to conform them to CustomNSError. For example, our APIError can conform to CustomNSError in the following way:

extension APIError: CustomNSError {

var errorCode: Int { code }

static var errorDomain: String { "APIError" }

}

This will group all API errors with the same status code.

The additional benefit of conforming to CustomNSError is that we can provide additional details that will show up in Firebase:

var errorUserInfo: [String: Any] {

[

"title": response?.title as Any,

"detail": response?.detail as Any,

]

}

Application crashes

An application crash is usually the worst outcome our app users can experience. And we should do everything in our power to prevent that.

Fail fast

However, avoiding crashes is not something to be done at any cost.

Generally speaking, when we can’t handle some condition in a meaningful way, we should expose this as an error to the user.

But, we are also limited by the programming language and ecosystem we operate in. Sometimes we need more expressivity in the language to represent some concept.

Let’s look at the following example:

class NamePicker {

private let names = ["John", "Josh", "Lucy", "Angela"]

private var selectedName: String

init() {

selectedName = names.first!

}

}

Generally speaking, force unwrapping is a pattern that we would like to avoid. But in this case, making init throwing wouldn’t convey the right message and it would pollute the code. It would require all upstream functions to be annotated with throws which would obscure the true value of genuine errors.

Here is another example:

let status = CVDisplayLinkCreateWithActiveCGDisplays(&link)

guard let link, status == kCVReturnSuccess else {

fatalError("Could not create display link. Return status: \(status)")

}

In this case, we believe that all preconditions for creating CVDisplayLink are fulfilled when this code is invoked. Therefore, instead of propagating optional CVDisplayLink through the codebase, we declare that this operation will crash the program allowing us to catch holes in our assumptions quickly.

The decision whether to crash, throw an error or return optional value needs to be made on a case-by-case basis. Here are some questions you should ask yourself to help you make this decision:

How likely is failure?

Is ignoring the failure leading to undefined behavior and even worse consequences such as data loss?

Have you ensured preconditions to be true in other parts of the code?

Is there a reasonable default value you can provide in case of failure

Would showing an error message to a user be better than to crash?

Some good resources on this topic include:

Additional crash logs

Seeing stack trace can very often lead to the clear root cause and conditions under which it happens. Unfortunately, for some of the crashes, this is not the case and any associated information might be useful to investigate, understand, reproduce, and fix the crash.

We can abstract this idea into the following protocol:

public protocol CrashInfoLogger: Sendable {

func log(_ message: String)

}

And we can implement Firebase crash info logging:

final class FirebaseCrashLogger: CrashLogger {

func log(_ message: String) {

Logger.app.log("\(message)")

Crashlytics.crashlytics().log(message)

}

}

And finally, we can provide a convenient extension for it:

public extension Logger {

static let crashInfo: CrashLogger = FirebaseCrashLogger()

}

This way, we can log some key events during the execution of the program. If the app crashes, these key events will be associated with the crash report in Firebase.

Following trends

Whether it is crashes or errors, some problems might never be reproducible in your local setup. For these issues, we often need to experiment with the fix.

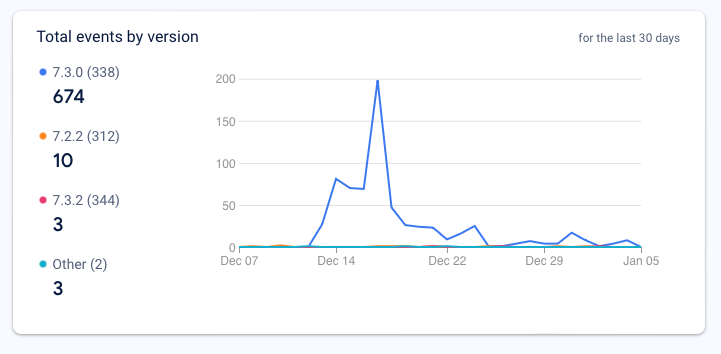

But we need some way to confirm if our fix helped or not. Firebase can provide valuable information about that. The following graph is an example of an issue that was fixed and confirmed by production data:

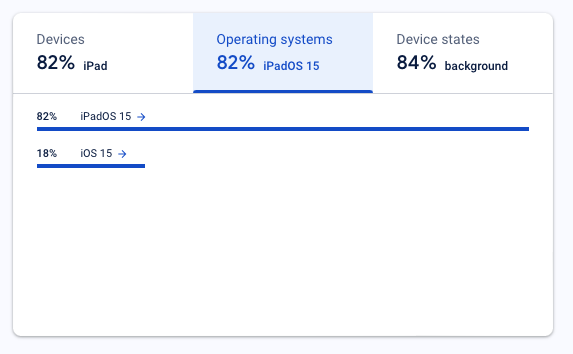

Firebase also provides a lot of valuable associated data. For example, this crash is only happening on iOS 15:

This is key information that can help us reproduce and fix the issue.

App Store Connect can also provide valuable information about your crash rate and how you compare to other apps in your category. It is important to keep an eye on the trend and make sure it is not growing.

Legal considerations

Logging errors, or even crashes to third-party systems can have a legal impact on the product you are making. Always check with your legal department what you are allowed to do.

Being proactive

Even if we follow all best practices and invest significant resources into this area, errors and crashes are almost impossible to avoid.

Therefore, it is important to be upfront about it with your clients and have open discussions about it.

It is more professional to inform your client that a new application version has introduced a crash, than a client coming to you with a complaining user report.

Clients are generally not interested in individual crashes. Instead, you can set up a cadance where you check this and inform your client in a public channel. This builds trust and understanding between the client and you and allows you to handle issues professionally.

Conclusion

Good error handling requires intention and care, but it is fundamentally not difficult. We hope this guide can help you on your road to better error and crash handling.